對英國人而言,無論你私底下對自己有多么滿意,也不應(yīng)該說I'm good……

By Anthony Daniels

戴樂竹 選注

On a recent short flight, an air hostess offered a snack[1] to an enormously fat American lady sitting next to me. “No, thank you,” she said, “I’m good.” If the question of what people eat is a moral one, she looked as if she hadn’t always been good, to put it mildly.[2]

Nowadays, when you ask people how they are, they are as likely to tell you that they are good as that they are well. It is as if you were inquiring after their moral rather than their bodily condition.

Of course, the two have seldom been more closely linked, health, diet and safety having replaced faith, hope and charity as the desiderata of the virtuous life.[3] Since so many modern illnesses are the consequence of overindulgence[4] in one thing or another, an inquiry after health is indeed a moral one. Oh Lord, we have eaten those things that we ought not to have eaten, and not eaten those things that we ought to have eaten.

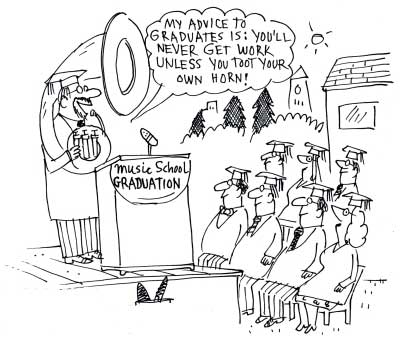

To English ears of a certain age, however, it still sounds strange for someone to say, in any sense whatever, that he is good. Surely, that is for someone else to say? One doesn’t blow one’s own trumpet[5], however pleased with oneself one secretly is.

“I’m good”—so often heard these days—has a complacent and almost boastful ring,[6] very different from that of “I’m well, thank you.” No one could say, “I’m good, thanks be to God[7].” No one is good by mere luck or good fortune, let alone by divine mercy.[8]

People who are good listen, often with rapt[9] attention, to their bodies. Their body tells them what to do and they do it. Alas, virtue is not always rewarded and, the perfect regimen notwithstanding, illness sometimes—indeed always, in the long-term—supervenes.[10] When that happens, do people say, “I’m bad”?

Not often. They revert to the adverbial—not well.[11] At most they say that they are feeling bad, which is not the same as being bad, of course. There is an asymmetry[12] in our moral assessment of ourselves: goodness comes from within, badness from without.[13] People, as a general rule, don’t ask for an explanation of their good behaviour: only their bad is mysterious to them. In many years of medical practice, no one has ever asked me, “Do you think it could be my childhood that makes me so nice, doctor?”

If the fat lady on the plane had wanted the snack, would she have said, “Yes please, I’m bad.”

Vocabulary

1. snack: 點心,小吃。

2. moral: 道德上的,精神上的;put it mildly: 說得婉轉(zhuǎn)些。

3. charity: 慈善;desiderata: 〈拉〉迫切需要得到之物,是desideratum的復(fù)數(shù)形式。

4. overindulgence: 過分沉溺于某事(尤指吃喝)。

5. blow one’s own trumpet: 自我吹噓,自吹自擂。

6. complacent: 自鳴得意的;boastful: 自夸的,傲慢的;ring: 特性,特質(zhì)。

7. thanks be to God: 感謝上帝。

8. divine: 神的;mercy: 憐憫,仁慈。

9. rapt: 全神貫注的,入迷的。

10. 哎,有德行并非總會得到報償,盡管踐行了最完美的養(yǎng)生法,疾病有時卻——長期來看的確總是會——意外出現(xiàn)。regimen: 生活規(guī)則,養(yǎng)生法;supervene: 接著發(fā)生。

11. revert to: 回歸;adverbial: 副詞。

12. asymmetry: 不對稱。

13. ……好是一種內(nèi)在品質(zhì),而壞與外界事物相關(guān)。without: adv. 在外面,在外部。

(來源:英語學(xué)習(xí)雜志)