在各種爭議聲中長大的80后一代,終于也開始登上歷史的舞臺。他們表現(xiàn)出與上一代人如此不同的特質(zhì):極其自信、樂觀、滿懷理想,但又自戀、不切實際、自尊心過強。在就業(yè)市場不景氣的大環(huán)境下,這一代人究竟是會不堪一擊,還是會表現(xiàn)出意想不到的抗壓能力?

By Judith Warner

王雪嬌 選注

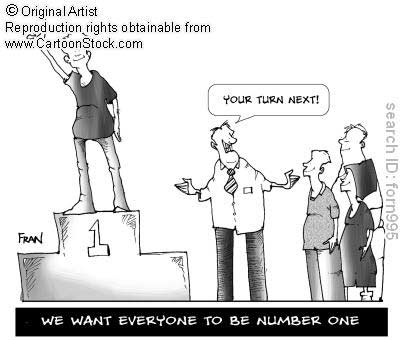

For the past few years, it’s been open season on Generation Y—also known as the millennials, echo boomers or, less flatteringly, Generation Me.[1] Once described by the trend-watchers Neil Howe and William Strauss as “the next great generation”—optimistic, idealistic and destined to do good—millennials, born between 1982 and 2002, have been depicted more recently by employers, professors and earnestly concerned mental-health experts as entitled whiners who have been spoiled by parents who overstoked their self-esteem, teachers who granted undeserved A’s and sports coaches who bestowed trophies on any player who showed up.[2]

As they’ve entered adulthood, they have inspired a number of books on how unmanageable they are in the workplace, with their ubiquitous iPods, flip-flops and inability to take criticism.[3] Stories abound about them as college students, requiring 24/7 e-mail access to professors and running to Mom and Dad for help with papers or to contest a bad grade.[4] A consensus has emerged that, psychologically, they’re a generation of basket cases: profoundly narcissistic and deprived of a sense of agency by their anxiously overinvolved parents.[5]

The behavior of many of this year’s college seniors might further fuel this story line.[6] They are graduating into a labor market decimated[7] by the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. The unemployment rate for early 20-somethings[8] is close to 20 percent. Increased applications to grad school have turned that option of sitting out the recession into a reach.[9] Even going into teaching—hyped a year ago as the most acceptable Plan B for high achievers turned off by (or turned away from) Wall Street—has become much tougher, as school districts have been devastated by budget cuts.[10] Yet despite the fact that the new graduates are in no position to pose conditions for employers, many are increasingly declaring themselves unwilling to work more than 40 hours a week. Graduates are turning down job offers in high numbers—essentially opting to move back home with their parents if the work offered doesn’t match their self-assessed market value.

According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, which every year surveys thousands of college graduates about their job prospects and work attitudes, fully 41 percent of job seekers this year turned down offers—the exact percentage that did so in 2007, when the economy was booming. And though less than a quarter of seniors who applied for work had postgraduation job offers in hand by late April (compared with 52 percent in 2007), many are still approaching work with attitudes suited for a full-employment[11] economy.

“Almost universally they want to find a job that’s not just a job but an expression of their identity, a form of self-fulfillment,” says Jeffrey Jensen Arnett, a Clark University psychology professor who interviewed hundreds of young people.

Not only do they believe these perfect jobs exist, but today’s recent graduates also think they’re good enough to get them. “They see themselves as really well prepared and supremely good candidates for the job market,” says Edwin Koc, director of research for the National Association of Colleges and Employers. “Over 90 percent think they have a perfect résumé. The percentage who think they will have a job in hand three months after graduation is now 57 percent. They’re still supremely confident in themselves.”

For critics, this is irrational exuberance, an example of group psychosis, proof that this generation is headed for a major crash.[12] “It’s not confidence; it’s overconfidence,” Jean Twenge, a professor in the department of psychology at San Diego State University and author of “Generation Me,” said. “And when it reaches that level, it’s problematic.”

But at a time when so many of their elders are struggling emotionally to keep their heads above water—dealing with layoffs or the fear of layoffs, feeling the walls closing in around them as whole professions contract in new and unanticipated ways—the children, you have to consider, might be on to something.[13] I interviewed nine students recommended to me by college professors and officials, yielding a picture of emerging adults with a striking ability to keep self-doubt—and deep discouragement—at bay[14]. Many were jobless, others were dissatisfied with their work or graduate-school choices, yet they didn’t blame themselves if life failed to meet their expectations. They didn’t call into question[15] their choices or competencies. It was as if all the cries of “Good job!” they heard as children armed them against[16] the repeated blows of frustration and rejection now coming their way.

“They’re extraordinarily optimistic that life will work out for them,” Arnett says. “Everybody thinks bright days are ahead and eventually they will find that terrific job.”

These emerging adults may be off-putting to a worried 40-something—their sense of entitlement and their lack of humility are somewhat hard to take—but they’re not necessarily maladapted.[17] On the contrary, with their seemingly inexhaustible well of positive self-regard, their refusal to have their horizons be defined by the limitations of our era, they just may bear witness to the precise sort of resilience that all parents, educators and pop psychologists now say they view as proof of a successful upbringing.[18]

It may be that this resilience—this annoying yet admirable ability to stay positive in depressing and frightening times—has nothing to do with the parents. Perhaps it’s a result, as some longtime observers of this generation have suggested, of growing up in an era of almost unremitting ambient anxiety: school years spent in the shadow of Columbine,[19] 9/11 and, lately, widespread parental job losses. Maybe chronic unease[20] has simply raised this generation’s tolerance level for stress, leaving it uniquely well equipped to deal with uncertainty.

Or maybe having a bulked-up ego really does serve as a buffer to adversity.[21] Just like the self-esteem gurus[22] always said that it would.

Vocabulary

1. open season: (針對某人或某事物)的言論開放期,此處指對Generation Y有很多批評聲的一段時期;Generation Y: 指1982年至2002年出生的一代人,區(qū)別于Generation X(1961年至1981年出生的一代),Generation Y又稱millennials或echo boomers,前者因為這代人是跨世紀(jì)的一代,后者因為是“嬰兒潮一代”(baby boomers)的后代,并造成了新一撥生育高峰;flatteringly: 諂媚地,奉承地。

2. 趨勢觀察家尼爾?豪和威廉?斯特勞斯曾將1982年至2002年期間出生的“跨世紀(jì)一代”稱為“下一個偉大的一代”,認(rèn)為這一代人樂觀、有理想、注定有所成就,但最近,雇主、教授和憂心忡忡的心理健康專家們認(rèn)為這一代人總是有權(quán)利哭哭啼啼,他們被家長寵壞,自尊心過強,他們從老師那兒得到的“A等”名不副實,他們只要參加運動就能從教練那兒得到獎品。

3. ubiquitous: 無處不在的;iPod: 指iPod音樂播放器;flip-flop: 人字拖。

4. abound: 大量存在;24/7 e-mail access to professors: 一天24小時、一周7天都能用電子郵件聯(lián)系到老師;contest a bad grade: 對低分提出質(zhì)疑。

5. 越來越多的人有相同的感受:從心理角度講,這一代人是不健全的人——他們極其自戀,被愛操心和過分干涉的父母剝奪了責(zé)任感和自主感。basket case: <美俚>精神極度緊張的人,精神瀕于崩潰的人。

6. college senior: (美國四年制大學(xué)的)四年級學(xué)生;fuel: 刺激,火上加油;story line: 故事情節(jié)。

7. decimate: 大批毀滅,極大削弱。

8. 20-something: 20多歲的人。

9. sit out: 坐在一旁不參加,此處指通過讀研逃避經(jīng)濟(jì)危機(jī);turn... into a reach: 變得有點兒夠不著,實現(xiàn)起來有點兒困難。

10. hype: 大肆宣傳;turn off: 使沮喪;turn away: 拒絕(進(jìn)入)。

11. full-employment: 充分就業(yè),指在某一工資水平之下,所有愿意接受工作的人都獲得了就業(yè)機(jī)會。

12. 對批評人士而言,這是非理性的情緒高漲,是集體精神失常的病例,證明這一代人正朝著一次重大打擊前行。

13. keep one’s head above water: 使自己免于負(fù)債(或失敗、損失等),湊合著活下去;contract: 收縮;be on to: 了解,知道。

14. keep at bay: 使(嚴(yán)重、危險或令人不快的)事物無法接近,防止某結(jié)果產(chǎn)生。

15. call sth. into question: 對……表示懷疑。

16. arm against: 武裝起來,從而免于遭受(打擊等)。

17. off-putting: 令人不快的;entitlement: 應(yīng)得的權(quán)利;maladapt: 使不適應(yīng)。

18. inexhaustible: 無窮無盡的,用不完的;have their horizons be defined: 他們的眼界被局限;bear witness to: 證明;resilience: 達(dá)觀,適應(yīng)力。

19. unremitting: 不間斷的,持續(xù)的;ambient: 周圍的,圍繞的;Columbine: 哥倫拜恩槍擊案。背景:1994年4月20日,美國科羅拉多州哥倫拜恩高中發(fā)生校園槍擊事件,兩名學(xué)生配備槍械和爆炸物進(jìn)入校園,槍殺了12名學(xué)生和1名教師,并造成其他24人受傷,兩人隨即自殺身亡,這起事件被視為美國歷史上最血腥的校園槍擊事件之一。

20. chronic unease: 長期的憂患和擔(dān)心。

21. 或者,他們不斷增強的自負(fù)也許真能在其面對逆境時起到緩沖作用。

22. guru: 專家,權(quán)威。

(來源:英語學(xué)習(xí)雜志)