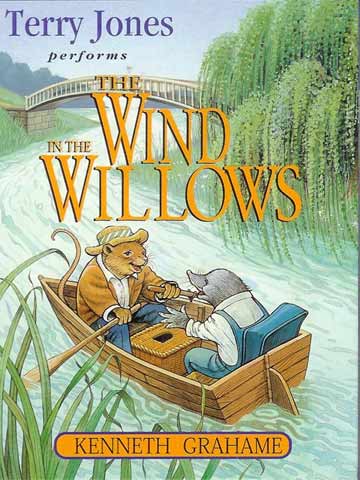

《楊柳風(fēng)》是格雷厄姆所著的一部妙趣橫生的經(jīng)典兒童小說,書中塑造了幾個可愛的動物形象:膽小怕事但又生性喜歡冒險的鼴鼠,熱情好客、充滿浪漫詩趣的河鼠,俠義十足、具有領(lǐng)袖風(fēng)范的老獾,喜歡吹牛、追求時髦的蟾蜍,敦厚老實的水獺。故事優(yōu)雅、詩意,充滿了趣味,捕獲了全世界讀者的心,甚至引起美國總統(tǒng)西奧多? 羅斯福的注意,他曾寫信告訴作者,自己把《楊柳風(fēng)》一口氣讀了三遍。

By Kenneth Grahame

安妮 選譯

|

Chapter 1 The River Bank (Excerpt) The Mole had been working very hard all the morning, spring-cleaning his little home. First with brooms, then with dusters; then on ladders and steps and chairs, with a brush and a pail of whitewash;[1] till he had dust in his throat and eyes, and splashes of whitewash all over his black fur, and an aching back and weary arms. Spring was moving in the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating[2] even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing. It was small wonder, then, that he suddenly flung down his brush on the floor, said “Bother!” and “O blow!” and also “Hang spring-cleaning!” and bolted[3] out of the house without even waiting to put on his coat. Something up above was calling him imperiously[4], and he made for the steep little tunnel which answered in his case to the gaveled carriage-drive owned by animals whose residences are nearer to the sun and air. So he scraped and scratched and scrabbled and scrooged and then he scrooged again and scrabbled and scratched and scraped, working busily with his little paws and muttering to himself, “Up we go! Up we go!” Till at last, pop! His snout[5] came out into the sunlight, and he found himself rolling in the warm grass of a great meadow. “This is fine!” he said to himself. “This is better than whitewashing!” The sunshine struck hot on his fur, soft breezes caressed his heated brow, and after the seclusion of the cellarage he had lived in so long the carol of happy birds fell on his dulled hearing almost like a shout. Jumping off all his four legs at once, in the joy of living and the delight of spring without its cleaning, he pursued his way across the meadow till he reached the hedge on the further side. “Hold up!” said an elderly rabbit at the gap. “Six pence for the privilege of passing by the private road!” He was bowled over[6] in an instant by the impatient and contemptuous Mole, who trotted along the side of the hedge chaffing the other rabbits as they peeped hurriedly from their holes to see what the row was about. “Onion-sauce! Onion-sauce!” he remarked jeeringly, and was gone before they could think of a thoroughly satisfactory reply. Then they all started grumbling[7] at each other. “How STUPID you are! Why didn’t you tell him...” “Well, why didn’t YOU say...” “You might have reminded him...” and so on, in the usual way; but of course, it was then much too late, as is always the case. It all seemed too good to be true. Hither and thither through the meadows he rambled busily, along the hedgerows, across the copses, finding everywhere birds building, flowers budding, leaves thrusting—everything happy, and progressive, and occupied. And instead of having an uneasy conscience pricking[8] him and whispering “whitewash!” he somehow could only feel how jolly it was to be the only idle dog among all these busy citizens. After all, the best part of a holiday is perhaps not so much to be resting yourself, as to see all the other fellows busy working. He thought his happiness was complete when, as he meandered aimlessly along, suddenly he stood by the edge of a full-fed river. Never in his life had he seen a river before—this sleek, sinuous[9], full-bodied animal, chasing and chucking, gripping things with a gurgle and leaving them with a laugh, to fling itself on fresh playmates that shook themselves free, and were caught and held again. All was a-shake and a-shiver—glints and gleams and sparkles, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble.[10] The Mole was bewitched, entranced, fascinated. By the side of the river he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spellbound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable[11] sea. As he sat on the grass and looked across the river, a dark hole in the bank opposite, just above the water’s edge, caught his eye, and dreamily he fell to considering what a nice snug dwelling-place it would make for an animal with few wants and fond of a bijou riverside residence, above flood level and remote from noise and dust.[12] As he gazed, something bright and small seemed to twinkle down in the heart of it, vanished, then twinkled once more like a tiny star. But it could hardly be a star in such an unlikely situation; and it was too glittering and small for a glow-worm. Then, as he looked, it winked at him, and so declared itself to be an eye; and a small face began gradually to grow up round it, like a frame round a picture. A brown little face, with whiskers. A grave round face, with the same twinkle in its eye that had first attracted his notice. Small neat ears and thick silky hair. It was the Water Rat! Then the two animals stood and regarded each other cautiously. “Hullo, Mole!” said the Water Rat. “Hullo, Rat!” said the Mole. “Would you like to come over?” enquired the Rat presently[13]. “Oh, it’s all very well to TALK,” said the Mole, rather pettishly[14], he being new to a river and riverside life and its ways. The Rat said nothing, but stooped and unfastened a rope and hauled on it; then lightly stepped into a little boat which the Mole had not observed. It was painted blue outside and white within, and was just the size for two animals; and the Mole’s whole heart went out to it at once, even though he did not yet fully understand its uses. The Rat sculled[15] smartly across and made fast. Then he held up his forepaw as the Mole stepped gingerly down. “Lean on that!” he said. “Now then, step lively!” and the Mole, to his surprise and rapture[16], found himself actually seated in the stern of a real boat. “This has been a wonderful day!” said he, as the Rat shoved off and took to the sculls again. “Do you know, I’ve never been in a boat before in all my life.” “What?” cried the Rat, open-mouthed: “Never been in a—you never—well I—what have you been doing, then?” “Is it so nice as all that?” asked the Mole shyly, though he was quite prepared to believe it as he leant back in his seat and surveyed the cushion, the oars, the rowlocks, and all the fascinating fittings, and felt the boat sway lightly under him.[17] “Nice? It’s the ONLY thing,” said the Water Rat solemnly, as he leant forward for his stroke. “Believe me, my young friend, there is NOTHING—absolute nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats. Simply messing,” he went on dreamily: “messing—about—in—boats; messing...” “Look ahead, Rat!” cried the Mole suddenly. It was too late. The boat struck the bank full tilt[18]. The dreamer, the joyous oarsman, lay on his back at the bottom of the boat, his heels in the air. |

第一章 在河邊(節(jié)選) 鼴鼠辛苦了一早上,給他的小屋子做春季大掃除。先是用掃帚,用雞毛撣子,然后是提著一桶涂料和一把刷子爬梯子、上臺階、踩椅子,直到干得腰酸背痛胳膊也疼,嗓子和眼睛里滿是灰塵,黑色的毛皮上滿是點(diǎn)點(diǎn)的白漿。春天的氣息已脈脈流動在周圍的空氣中、在腳下泥土里,甚至他這間陰暗的小房子里也充滿了春天那生機(jī)勃勃而又不安分的騷動情緒。因此,他會突然扔下刷子,嘟囔了一聲:“讓春季掃除見鬼去吧!”也不奇怪。然后便不等穿好衣服,就一溜煙地跑出屋子了。頭頂上有什么東西不容分說地在召喚他,他向那條通向地面的陡峭的小地道跑去,不過這條行車道是靠近陽光和空氣居住的動物們的天下。于是他那小爪子忙碌了起來,又鉆又摳、又扒又拱,同時給自己小聲鼓勁兒,“爬上去!爬上去!”最后,他那尖鼻子噗地一聲碰觸到了陽光,一下滾進(jìn)了一片廣闊、溫暖的草地。 “這太好了!”他自言自語說,“比刷墻舒服多了!”太陽照在他的皮毛上熱烘烘的,柔和的風(fēng)撫摸著他的熱額頭。他在地窖里與世隔絕,日子一長,耳朵就不靈了,鳥兒們快活的歌聲落進(jìn)耳朵里像是在吶喊,驚得他四腳騰空蹦了起來,心里滿是生機(jī)勃勃的快感和無需做春季掃除的喜悅。他穿過草場來到了對面的樹籬。 “站住!”一只年長的兔子堵在樹籬缺口上喊道,“私人領(lǐng)地,交六便士才能過去!”傲慢的鼴鼠失去了耐心,突然一下把兔子撞倒,沿著樹籬邊一溜煙跑過去。這小騷亂使得別的兔子都匆匆從他們的洞中探出頭來,想瞧一瞧究竟發(fā)生了什么事情。“洋蔥醬!洋蔥醬!”鼴鼠輕蔑地笑道。沒等兔子們想出一個滿意的答案,他就跑得沒影兒了。兔子們開始埋怨彼此:“你怎么這么笨!你為什么不告訴他……”“為什么你不說……”“你原可以提醒他……”嘟囔聲不絕,就跟往常一樣。但是,當(dāng)然已經(jīng)來不及做什么補(bǔ)救措施了——之前的情況往往也是這樣。 一切似乎都好得難以置信。他在草場上匆匆忙忙地這兒走走,那兒逛逛,或是沿著樹籬,或是穿過灌木林,到處都有筑巢的鳥兒,含苞的花兒和悄悄探出頭的芽兒—— 一切都是這么快樂,在前進(jìn)著,在忙碌著。他不知道為什么沒有感覺到心里不安,良心也沒有責(zé)備他:“刷墻去!”他在這些忙忙碌碌的鄰居之間當(dāng)了個大懶蟲,不知道為什么卻覺得快活。畢竟,一個假期最愉快的時刻,似乎不在于自己休息好了,而是看著別人忙忙碌碌地工作。 他漫無目的地走著,來到了一條水源充沛的河岸邊,他突然站住了——他從來沒有見過河,這個彎曲、壯實、油滑發(fā)亮的動物在追逐著、歡笑著,咯咯地笑著抓住一個東西,又哈哈笑著扔掉,向新的游伴撲去。新游伴剛擺脫它又被它抓住。一切都在搖擺、顫動明亮、閃光、耀眼、嘩啦嘩啦,打旋、說閑話、冒泡。鼴鼠看得丟了魂,從來沒有覺得這么快樂過。他沿著河邊走,像個年幼的小不點(diǎn)走在大人身邊,聽他們講有趣的故事,聽得入了迷。終于鼴鼠走累了,坐在河邊,但是河水還在絮叨個沒完,講述著世界各地最有趣的故事。這些故事從遙遠(yuǎn)的地心開始,河水將它們帶給永不滿足的海洋。 他坐在草地上向河對岸望去,剛高過水面處有一個小黑洞吸引了他的眼球。他幻想著,對于一個要求不高而又喜歡在河邊有一間小巧雅致的住所的動物而言,那地方倒是個舒適愜意的住處——恰好高過水平面又遠(yuǎn)離塵囂。正當(dāng)他盯著這個黑洞看的時候,小黑洞的中心似乎有一個發(fā)亮的小東西,一下發(fā)光一下光滅了,真地就像一顆小星星似的。但是絕對不可能是星星,而且它太小太亮了也不像是熒火蟲。然后鼴鼠再一瞧,這小星星似乎在向他眨巴眼。哦,原來這是一只眼睛啊,然后眼睛周圍的小臉蛋開始慢慢顯現(xiàn)出來,就像給圖加了一個框。 一張褐色的小臉蛋,邊上帶有胡須。 一張一本正經(jīng)的圓臉,眼睛里閃爍著最初吸引了他的那種亮光。 整齊的小耳朵,絲綢般光滑的厚皮毛。 這是一只河鼠! 兩只動物都站著不動,謹(jǐn)慎地打量著對方。 “你好,鼴鼠!”河鼠說。 “你好,河鼠!”鼴鼠說。 “愿意過來玩嗎?”河鼠立即問道。 “哼,說得倒輕巧,”鼴鼠耍著小性子,他還不熟悉這條河流和河邊的生活方式。 河鼠二話不說,彎下腰解開一條繩子,使勁一拉,輕身躍上了一條小船。鼴鼠之前沒有注意到小船的存在。小船外側(cè)漆成了藍(lán)色,內(nèi)側(cè)漆成了白色,大小正好能容下兩只小動物。鼴鼠的心立即向小船飛去了,盡管他還不完全明白小船的作用。 河鼠輕巧熟練地劃著船,越劃越快。然后在鼴鼠小心翼翼往船上踏時,他伸出了前爪,“扶著點(diǎn)!好,現(xiàn)在跳上來。”鼴鼠驚訝地發(fā)現(xiàn)自己坐在了一條真正的小船的船尾,心里一陣狂喜。 河鼠推船離岸,又劃起了槳。鼴鼠感慨道:“今天真是快活的一天啊!你知道嗎,我這輩子還沒坐過船呢!”“什么?”河鼠張開嘴大叫著,“從來沒有坐過……你從來沒有……呃,我……那你干什么去了?” “坐船有這么好嗎?”鼴鼠害羞地問道,盡管他悠閑地靠在座位上,環(huán)視船邊的氣墊、船槳、槳架以及其他迷人的設(shè)備,享受船在他身下輕輕搖擺的感覺,心里早就知道這問題的答案了。 “好?只有在船上才算是生活。”河鼠一邊彎下身子劃槳,一邊嚴(yán)肅地說,“相信我,我年輕的朋友,除了在船上忙來忙去,就再也沒有其他什么值得做的事,絕對沒有了。只有在船上忙來忙去,”他陷入了自己的沉思中,“在……船上……忙來忙去;忙……” “注意前面,河鼠!”鼴鼠突然大叫。 但是已經(jīng)來不及了。小船全速地撞上了河岸。那個做白日夢的快活的劃槳人四腳朝天地倒在船底。 (來源:英語學(xué)習(xí)雜志) |

|

Vocabulary: 1. pail:〈美〉桶,水桶;whitewash:(尤指刷墻用的)石灰水,白涂料。 2. penetrate: 穿透;滲入。 3. bolt: 奔,躥。 4. imperiously: 專橫地,傲慢地。 5. snout: 長鼻子。 6. bowl over: 撞倒。 7. grumble: 發(fā)牢騷,埋怨。 8. prick: 刺,戳。 9. sinuous: 蜿蜒的,彎彎曲曲的。 10. glint: 閃爍,閃光;rustle: 沙沙作響。 11. insatiable: 不能滿足的。 12. snug: 溫暖舒適的,安逸的;bijou:(尤指建筑物)小巧雅致的。 13. presently: 馬上,立即。 14. pettishly: 耍小孩子脾氣地,使性子地。 15. scull:(用槳)劃船。 16. rapture:〈正式〉狂喜。 17. cushion: 起墊子作用的東西;rowlock:〈英〉 槳架。 18. full tilt:〈非正式〉 全速地,全力地。 |