Can we work together for economic inclusion?

|

|

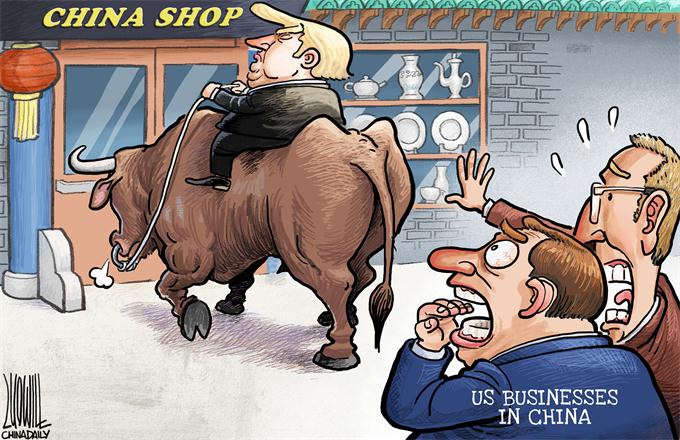

CAI MENG/CHINA DAILY |

Editor's Note: This week we are presenting a year-end review of the global economy, China's economy, society and diplomacy; and the international situation. Today three top economists look at the state of the global economy and give their outlooks for 2017.

In 2016, the world's attention was focused on major political developments in the European Union, the United States and some other countries, where voters have expressed deeply held concerns about trade, migration and structural labor-market changes.

But, from an economic perspective, 2016 was a fairly quiet year: the global economy continued its slow recovery, with economic activity in the US, the EU, and emerging markets gradually improving despite some remaining vulnerabilities. And even low-income economies that have struggled to adjust to falling commodity prices may receive a small boost, given recent price increases.

Remarkably, financial markets have so far taken the year's political upheavals in their stride. Indeed, the prospect of a more expansive fiscal stance in the US has raised expectations of global growth and inflation in the near future. This signals possible relief for advanced economies' central banks, which have carried most of the economic-policy burden during the years of slow recovery since the 2008 global financial crisis.

As the International Monetary Fund has argued for some time, a resurgence of growth requires support from fiscal policy in countries that can afford it, supported by monetary policy and structural reforms aimed at lifting productivity and growth.

Several factors in 2017 could move the global economy toward stronger, sustained growth. For starters, Germany will assume leadership of the G20, and will likely push for structural reforms and resilience-strengthening measures in the world's largest economies. China, meanwhile, will continue to reorient its economic model away from exports and toward domestic demand. And we should expect to see more youthful dynamism across many Asian and Latin American economies. The new US administration will emphasize corporate tax reform and infrastructure investment.

But, of course, the same forces that have driven this year's political developments will continue to pose challenges in 2017. For example, technological progress and winner-take-all markets are widening income inequality within many countries, even as global incomes are converging. In major advanced economies over the past two decades, the top 10 percent of earners' incomes increased by 40 percent, while incomes for those at the bottom grew only modestly.

Another increasingly complex issue that the international community will have to confront is migration, which is being amplified by geopolitical pressures around the globe. While migrants and refugees can bring substantial benefits to host countries, their arrival in new communities can increase fears of economic and cultural change.

Across a range of countries, a growing number of people believe that policymakers have lost touch with their interests and welfare. They maintain that tighter restrictions on cross-border movement of goods, capital and people will restore their own employment prospects and economic security.

But a retreat from free trade and open markets would only jeopardize the unprecedented gains in welfare and living standards achieved in recent decades-and low-income households would be hit the hardest. The challenge, therefore, is to preserve the gains from economic openness while addressing inequalities head-on.

The IMF, for its part, considers a more equitable income distribution to be not only sound social policy, but sound economic policy, too. Our research shows that reducing high inequality makes economic growth more robust and sustainable over the long term.

I believe that there are several steps countries can take to address inequality. For starters, governments can increase their direct support for lower-skill workers, especially in geographic regions that have been most affected by automation and outsourcing. Specifically, governments should increase their public investments in healthcare services, education and skills training; and they should make an effort to improve occupational and geographic mobility. Every country should understand the need for lifelong education to prepare current and future generations for fast-changing technologies.

Second, governments should strengthen social safety nets, especially for families, by promoting affordable childcare, parental leave, access to healthcare, and workplace flexibility. They can also implement tax reforms and legal minimum wages to support lower-income earners, and create tax incentives to bring more women into the job market.

Third, governments should be committed to ensuring economic fairness in order to restore social trust and bolster public support for reforms. Specifically, governments should foster more competition in important industries that lack it, crack down on tax evasion, and prevent business practices that shift profits to low-tax locations.

These are just some of the policies that can improve economic inclusion, and more should be done to identify additional measures-and implement them effectively. This is a task not only for politicians and public servants, but also for the economics profession as a whole.

I have no doubt that the political developments in 2016 will focus policymakers' minds on helping those who have benefited least from economic integration, or have been displaced by technology-driven labor-market changes. We can raise the income floor only by coming together and moving quickly to build a stronger, more inclusive global economy. That is both the challenge and the opportunity of 2017. We must move fast-and together.

The author is managing director of the International Monetary Fund.

Project Syndicate