Baa, baa, lab sheep

There are many celebrity animals, but at the moment, none is more famous in China than a woolly creature that lives in Tianjin. Liu Zhihua has the story.

At the TEDA International Cardiovascular Hospital in Tianjin, there is a very famous animal of the woolly persuasion. His name is Tianjiu, a sheep whose name has hogged headlines in the mainstream media, and whose photograph went viral on the Internet.

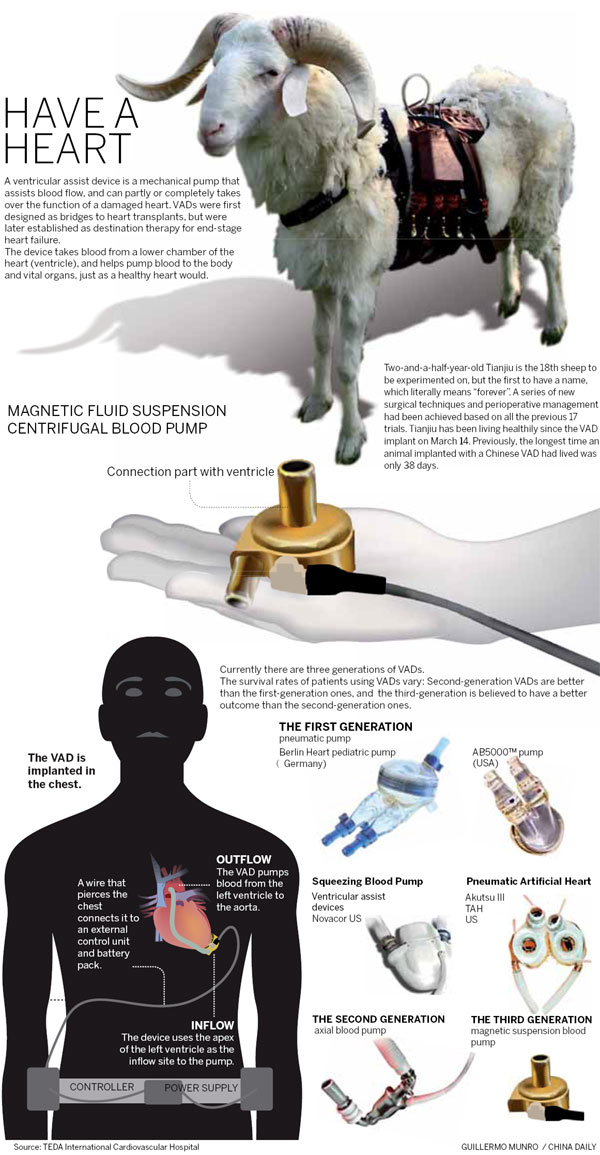

The 2.5-year-old animal is famous because he is wearing a ventricular assist device (VAD) that was developed and made in China and is doing very well. The device was implanted on March 14, and Tianjiu is still living, healthily.

Previously, the longest time an animal implanted with a Chinese VAD had lived was only 38 days.

The hospital launched the program in 2009, together with a branch institute of China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology.

"Such a successful trial has never been done before in China. It is absolutely a great breakthrough," says Liu Xiaocheng, president of the hospital and team leader of the VAD program.

"Based on this success, we are going to carry out group animal trials and then clinical human trials when we get approval from health authorities. We will likely find a permanent treatment for heart failure through the use of VADs."

Heart failure is a worldwide medical issue. The condition occurs when the heart cannot pump enough blood to cater for a healthy body. A heart transplant is currently the only reliable treatment for end-stage heart failure.

Patients waiting for a heart transplant may not last until they find a suitable donor, because demand always exceeds supply, Liu says.

Because of this, many doctors see VAD as an alternative lifeline for people with end-stage heart failure, especially when the patient cannot have a heart transplant.

In China, there is an estimated population of 16 million heart failure patients currently, many of whom are in the end stage. However, only about 100 heart transplants are conducted each year, Liu notes.

VAD is a mechanical pump that assists blood circulation and can partly or completely take over the function of a damaged heart, Liu adds.

Since the first VAD got United States Food and Drug Administration's approval in 1994 for clinical use, some countries, including the US, Japan and Germany, have developed various VADs and have used them either as a bridge to heart transplants, or as alternative therapy.

Although scientists in Beijing implanted VADs in animals as early as in the 1980s, about a decade later after similar experiments in the US, China had yet to develop its own domestically produced VADs for clinical tests.

"Making a VAD is not only a medical, but also an engineering and technology challenge," Liu says. "We lag behind international levels, although a lot of professionals have invested effort for the cause."