|

|

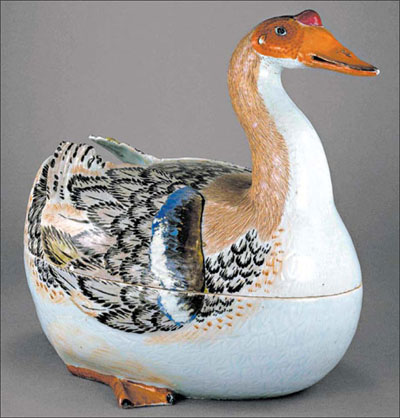

Major works of porcelain are on exhibit in Beijing through January 6. A goose-shaped tureen from the Qing dynasty. Trustees of the British Museum |

|

|

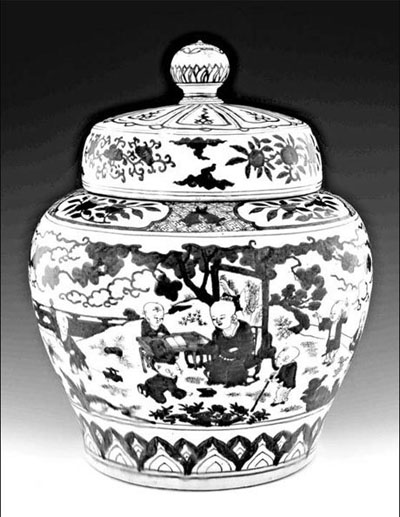

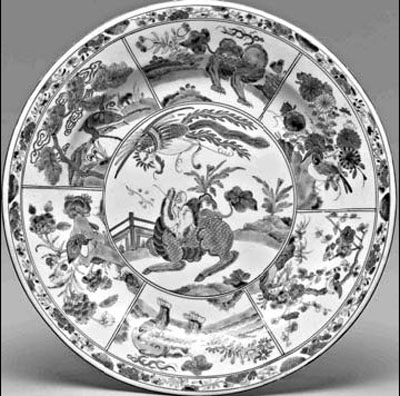

A jar from the Ming dynasty is decorated with boys playing; and a plate featuring panels of landscape and monsters, below. Photographs by Trustees of the British Museum |

|

When the National Museum of China and the British Museum decided to collaborate on an exhibition here that would celebrate two important 2012 events - the London Olympics and the Chinese museum's centennial - they chose to focus on something that played a vital role in the fortunes of both nations: porcelain.

Related: China Guardian 31st Quarterly Auction ready to go

"China is incredibly proud that they found the technology to make porcelain," said Jan Stuart, head of the Asia department at the British Museum. "They wanted to highlight that for the international and local audience."

It was potters of the Song dynasty (960-1279) at Jingdezhen who discovered the secret of porcelain production when they added kaolin to the China stone used to make other ceramics and raised kiln temperatures to above 1,300 Celsius. The resulting material was strong, translucent and brilliant white, allowing for the production of elaborate vessels that had unparalleled potential for decoration, and for which there was unprecedented demand.

"Porcelain really was the first global good," Ms. Stuart said. "It was crated all over, part of the modern economy and the silver trade."

Porcelain made a spectacular impact nearly everywhere it went, its ethereal beauty and startling strength leading some to ascribe magical powers to it. In one Southeast Asian culture, it was thought to be the progeny of shooting stars; in others it was said to heal the sick and call down spirits.

The Middle East - which had its own sophisticated ceramics tradition - had long been the biggest overseas market for Song ceramics. It quickly took to porcelain, and the Chinese Muslim merchants who managed this seaborne "ceramics route" introduced the Middle Eastern cobalt that enabled the creation of Ming China's signature blue and white porcelain.

As demand boomed, Jingdezhen's workshops grew increasingly specialized - each porcelain piece passed through the hands of roughly 70 craftsmen, with some workers just painting blue rims on bowls.

At least one porcelain piece had reached Europe by 1300 but significant exports did not begin until the late 1500s, when first Portuguese and then Dutch and English traders began shipping it - often as ballast on boats full of tea and silk - and ignited the "passion for porcelain," which has given the current show its name.

The exhibition, which runs until January 6, was also curated by the Victoria & Albert Museum, the first time these major institutions have jointly displayed their Chinese porcelain collections.

The first part of the show is devoted to Ming and Qing export ceramics. While most were blue and white, decorated according to Chinese taste, some were special commissions for wealthy Europeans.

One of the oldest is a blue and white serving dish (1520-30) made for a Portuguese customer that is decorated with peonies and the letters "IHS."

The monogram - a Latin abbreviation for Iesus hominum salvator (Jesus, savior of mankind) - is associated with the Jesuits, but the plate pre-dates their arrival in China, and even the founding of their order in 1534.