當(dāng)前位置: Language Tips> 英語學(xué)習(xí)專欄

分享到

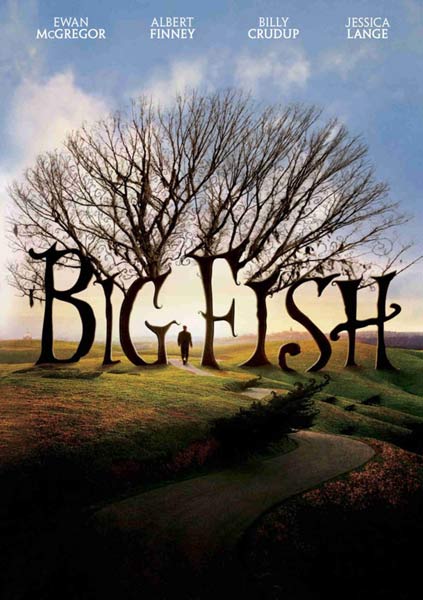

愛德華?布魯姆擁有神奇的經(jīng)歷,他常常講述自己年輕時如何從一個小鎮(zhèn)出發(fā)游歷世界,如何遇到巨人、巫婆、變形人、連體歌手等奇人,如何閱盡人間無數(shù)滿載而歸。而他的兒子威廉?布魯姆卻覺得自己老爸太浮夸,所講之事不可能是真實的。直到老爸身患癌癥,威廉才意識到自己對父親了解太少,父親的一生對他來說更是撲朔迷離、真假參半。當(dāng)他根據(jù)父親的故事去尋找父親傳奇一生的足跡時,他慢慢接觸到以前的人、事、物,開始切身體會到父親一生的輝煌與失敗。

“你能相信嗎?我想這就是我的命。大池塘里的一條大魚——那就是我想要的。那就是從有生第一天起我就想要的,”愛德華?布魯姆如是說。當(dāng)我們隨著《大魚奇緣》幻妙的筆觸瀏覽他的一生時,他仿佛從小就具有神奇的力量,注定要成為這萬千廣闊世界中的“一條大魚”。在小說結(jié)尾,愛德華驀然回首,他發(fā)現(xiàn)自己一直在孜孜所求的“偉大”原來就在自己的家里,那就是“被自己的兒子所深愛”,父與子之間的裂痕得以修復(fù)。

By Daniel Wallace

安妮 選 言佳 譯

|

On one of our last car trips, near the end of my father’s life as a man, we stopped by a river, and we took a walk to its banks, where we sat in the shade of an old oak tree. After a couple of minutes my father took off his shoes and his socks and placed his feet in the clear-running water, and he looked at them there. Then he closed his eyes and smiled. I hadn’t seen him smile like that in a while. Suddenly he took a deep breath and said, “This reminds me.” And then he stopped, and thought some more. Things came slow for him then if they ever came at all, and I guessed he was thinking of some joke to tell, because he always had some joke to tell. Or he might tell me a story that would celebrate his adventurous and heroic life. And I wondered, what does this remind him of? Does it remind him of the duck in the hardware store? The horse in the bar? The boy who was knee-high to a grasshopper? Did it remind him of the dinosaur egg he found one day, then lost, or the country he once ruled for the better part of a week? “This reminds me,” he said, “of when I was a boy.” I looked at this old man, my old man with his old white feet in this clear-running stream, these moments among the very last in his life, and I thought of him suddenly, and simply, as a boy, a child, a youth, with his whole life ahead of him, much as mine was ahead of me. I’d never done that before. And these images—the now and then of my father—converged, and at that moment he turned into a weird creature, wild, concurrently young and old, dying and newborn. My father became a myth... In Which He Speaks to Animals My father had a way with animals, everybody said so. When he was a boy, raccoons ate out of his hand. Birds perched on his shoulder as he helped his own father in the field. One night, a bear slept on the ground outside his window, and why? He knew the animals’ special language. He had that quality . Cows and horses took a peculiar liking to him as well. Followed him around et cetera . Rubbed their big brown noses against his shoulder and snorted, as if to say something specially to him. A chicken once sat in my father’s lap and laid an egg there—a little brown one. Never seen anything like it, nobody had. His Great Promise They say he never forgot a name or a face or your favorite color, and that by his twelfth year he knew everybody in his home town by the sound their shoes made when they walked. They say he grew so tall so quickly that for a time—months? The better part of a year?—he was confined to his bed because the calcification of his bones could not keep up with his height’s ambition, so that when he tried to stand he was like a dangling vine and would fall to the floor in a heap. Edward Bloom used his time wisely, reading. He read almost every book there was in Ashland. A thousand books—some say ten thousand. History, Art, Philosophy. Horatio Alger . It didn’t matter. He read them all. Even the telephone book. They say that eventually he knew more than anybody, even Mr. Pinkwater, the librarian. He was a big fish, even then. |

在我父親快要走到生命終點之時,我們駕車出游過幾次。其中一次,我們停在一條河的附近,我們步行到河岸邊,在一棵老橡樹的樹陰下坐了下來。 幾分鐘之后,我父親脫下鞋和襪子,把雙腳伸進(jìn)清澈的水流中,看著它們。然后他閉上雙眼,臉上露出了微笑。我有段時間都沒見他這么笑過了。 突然,他深吸了一口氣,開口說道:“這提醒了我。” 隨后他就停了下來,還在想些什么。那時,他想事情總是很慢,如果最后他能想出來的話。我猜,他可能想說一個笑話,因為他總是有笑話可說。或者,他也許想給我講個故事,頌揚(yáng)他那充滿冒險和英雄色彩的一生。我很好奇,(此情此景)究竟提醒了他什么?是不是令他想起了五金店的那只鴨子?又或是酒吧里的那匹馬?那個只及蚱蜢膝蓋高的男孩?還是讓他想起了那個他曾經(jīng)找到卻又遺失的恐龍蛋,或是他曾經(jīng)統(tǒng)治了大半個星期的國家? “這讓我想起了,”他說道,“我還是個小男孩的時候。 我看著這位老人,我的父親,他那雙又老又白的腳浸在清澈的河流中——在他生命最后時期的這些時刻中,我還突然想到了他的一生,僅僅是作為一個男孩,一個少年,一個青年,他的一生就這樣在他的面前展開,就像我的一生鋪展在我面前一樣。我從來沒有以這樣的方式看待過父親。這些形象——我父親的過去和現(xiàn)在——重疊在一起,就在那一刻,(在我眼中)他變成了一個神秘奇妙的生靈,帶著些許野性,既年輕又蒼老,正邁向死亡,卻又迎來重生。 我父親成為了一個神話…… 他與動物說話 我的父親善于跟動物們打交道,大家都這么說。當(dāng)他還是個孩子時,浣熊們舔食他手上的食物。當(dāng)他在田里幫自己父親干農(nóng)活時,鳥兒們會落在他的肩上。一天夜里,一只熊睡在他窗外的地上。為什么會這樣呢?因為他懂得動物們的特殊語言。他有這種能耐。 母牛和馬兒們也特別喜歡他,比如會跟在他后面團(tuán)團(tuán)轉(zhuǎn),等等。它們用自己的褐色大鼻子蹭著他的肩膀,呼哧呼哧噴著鼻息,好像要對他說些特別的悄悄話。有一次,一只母雞蹲在我老爸的膝上,下了一個蛋,那是一個小小的、褐色的蛋。從來沒見過這樣的事,沒有人見過。 他的遠(yuǎn)大前程 他們說,他從不會忘記一個名字、一張臉,或是你最喜愛的顏色。因此,當(dāng)他12歲時,他就能通過走路時鞋子發(fā)出的聲音來認(rèn)出自己家鄉(xiāng)的每一個人。 他們說,他在一段時間內(nèi)長得很高很快——可能幾個月?或大半年?——他被迫呆在床上,因為他骨頭的鈣化速度跟不上他個頭的增高,以至于當(dāng)他試著想站起來的時候,他就像一根搖擺的蔓藤一樣,會摔倒在地板上,癱成一團(tuán)。 愛德華?布魯姆很明智地利用了這段(躺在床上的)時間,他都用來讀書了。他幾乎讀遍了阿什蘭鎮(zhèn)的每一本書。有一千本,有人說是一萬本。歷史、藝術(shù)、哲學(xué),還有霍雷肖?阿爾杰的書。無論什么書,他都會去讀,甚至是電話簿也不例外。 他們說,最終他知道得比任何人都多,甚至超過了圖書管理員平克沃特先生。甚至到那時,他就已經(jīng)成為一條大魚了。 (來源:英語學(xué)習(xí)雜志 編輯:丹妮) |

|

Vocabulary: 1. the better part of: 大部分,大半。 2. converge: (向某一點)相交,匯合;concurrently: 同時發(fā)生地,共存地。 3. have a way with: 善于處理,有能力應(yīng)付。 4. quality: 品性,才能。 5. et cetera: 等等,及其他等等(略作etc.)。 6. rub: 摩擦;snort: 噴鼻息,自鼻孔噴氣做聲。 7. calcification: (人體組織的)鈣化;dangling: 晃來晃去的,懸蕩著的;heap: (一)堆,(一)團(tuán)。 8. Horatio Alger: 霍雷肖?阿爾杰(1832—1899),美國兒童文學(xué)作家,以描寫白手起家、勤奮致富的貧困孩子的故事而著名。 |

分享到

關(guān)注和訂閱

翻譯

關(guān)于我們 | 聯(lián)系方式 | 招聘信息

電話:8610-84883645

傳真:8610-84883500

Email: languagetips@chinadaily.com.cn