Scientists probe Ebola's deadly genes for clues

Scientists tracking the spread of Ebola across West Africa released 99 sequenced genomes of the deadly and highly contagious hemorrhagic virus on Thursday, hoping the data might accelerate diagnosis and treatment.

As a sign of the urgency and danger, five of the 60 international co-authors who helped collect and analyze the viral samples have died of Ebola already this year, the journal Science reported.

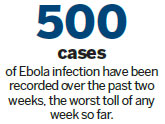

The World Health Organization said the past week had seen the highest increase of Ebola cases since the outbreak began, more evidence that the crisis is worsening. In an update on Friday, the UN health agency said more than 500 cases were recorded over the past week, by far the worst toll of any week so far.

Never before has there been an Ebola outbreak so large, nor has the virus - which was first detected in 1976 - ever infected people in West Africa until now.

"We've uncovered more than 300 genetic clues about what sets this outbreak apart from previous outbreaks," said Stephen Gire, a research scientist in the Sabeti lab at the Broad Institute and Harvard University.

"Although we don't know whether these differences are related to the severity of the current outbreak, by sharing these data with the research community we hope to speed up our understanding of this epidemic and support global efforts to contain it."

Ebola spreads through close contact with the bodily fluids of infected people when they are showing symptoms, such as fever, vomiting or diarrhea.

It can also be contagious after a person dies, and health officials have warned that touching corpses during funeral rites can be a key route of transmission.

West Africa's outbreak began in Guinea early this year, and then spread to Liberia in March, Sierra Leone in May and Nigeria in late July.

Researchers took samples of the virus from 78 patients in Sierra Leone during the first few weeks of the outbreak there.

They released 99 sequences, because they sampled some of the patients twice to show how the virus could evolve in a single person.

Scientists focused some of their study on a group of 12 individuals who were infected in Sierra Leone while attending the funeral of a traditional healer who had come into contact with Ebola patients from Guinea.

Their story was first told to an AFP reporter in Kenema, Sierra Leone, last week.

Samples taken from the 12 funeral attendees show that the Sierra Leone outbreak stemmed from two genetically distinct viruses circulating in Guinea at the time, Science reported.

This suggests "the funeral attendees were most likely infected by two linages then circulating in Guinea, possibly at the funeral", the report said.

The mourners included a young pregnant woman. Soon after, she was hospitalized with a fever and miscarried, but she survived. She was Sierra Leone's first confirmed case of Ebola in the outbreak that swept West Africa.

Researchers said they believe the virus spreads via an animal host, possibly a kind of fruit bat that has a natural range from central Africa - where Ebola has caused human outbreaks before - to Guinea in the continent's far west.

(China Daily 08/30/2014 page12)