HIV-positive convicts: Prisoners of prejudice

By Xu Lingui (China Daily)Updated: 2007-07-09 07:19

Fan Zongyu still remembers how nervous he felt when he first faced a row of HIV-positive convicts held in Qingliu Prison, in East China's Fujian Province.

For the last two years, Fan, who has been a prison warden for 18 years, and six of his colleagues have been running a special correctional division for HIV-infected male criminals in the Qingliu Prison.

|

|

"Many think the job is like 'skating on thin ice between life and death', but we have learnt to get used to it," Fan says with a laugh, as he directed inmates out of their cells for morning exercises.

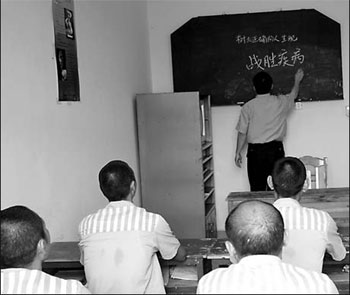

Lined up in three rows on a basketball court, they go through their exercise routine according to the directions shouted by the guards. Their muscles bulge beneath their blue-striped T-shirts, which serve as the uniform for prisoners nationwide.

When their exercises are completed, they spend free time chatting with guards or sitting in the grass, basking in the sunshine beneath a large blue sign that reads: "cherish life, overcome illness".

"These inmates look and can live like ordinary people. Nevertheless, we have started extra sport programs for them and cook them nutritious meals," Fan says.

The prison monitors the immune systems of inmates living with HIV with twice-a-year checkups.

Fan says that so far, only two inmates who had developed AIDS symptoms were granted medical parole and admitted into the best hospital in the provincial capital of Fuzhou.

Nestled among lush low-lying mountains, the Qingliu Prison is the only grandiose, modern establishment in the sleepy, ancient town of Linshe.

It is such an uneventful place that the locals still talk about Mao Zedong leading the Red Army through the town in the 1930s. They say Mao composed a poem here to demonstrate his faith in Communist victory.

Some 75 years after Mao's stopover, Fan and his colleagues have embarked on their own Long March - to rehabilitate prisoners who, as AIDS victims, face double doses of discrimination.

Given the negative social stigma attached to HIV/AIDS in China, Fan's task, in a sense, is no less arduous than Mao's revolution.

"The key to success is to give them (HIV-positive inmates) enormous faith and show zero discrimination," says Fan, recalling an incident of failure that happened soon after the division was formed in 2005.

To protect their staff, prison authorities ordered the guards to wear head-to-toe protective clothing and had a glass shield erected in the conversation room.

"But we found it extremely hard to talk to inmates when we appeared behind a glass wall dressed like medics during the SARS crisis," Fan says.

"I remember howls of despair and defiance echoing up and down the cells all day, and the inmates openly challenged us," says Wu Yongchun, a colleague of Fan's in his 20s. Wu adds that the situation wasn't resolved until the prison guards cast off their protective clothing and unfounded fears.

He says that when mutual respect was restored, guards and inmates were finally able to casually talk face to face.

"Deep down, they have very low self-esteem and desperately need care and concern," Fan says.

In Qingliu, HIV-positive inmates are entitled to free medication and better housing conditions. Any room in the two-story building has four single, wooden beds set side-by-side. And prisoners here enjoy the comforts offered by electric fans, color television and a spacious window through which they can see a long stretch of green grass and mountains.

While the better-than-average accommodations help, Fan says that what HIV patients need most is faith.

An inmate surnamed Huang was only 19 years old when he was sent to Qingliu to serve out his sentence of more than 19 years for robbery and theft. He had contracted HIV through unprotected sex.

|

|

Upon receiving his test results, Huang was "thunderstruck and felt his fate was sealed", Wu says, adding that the young man often lamented that "my life won't last as long as the prison term".

"As guards, we believe that the day is not far off when there will finally be a cure for AIDS, and most of the HIV-affected inmates will be able to walk out of the prison," Fan says. "We try our best to convince the inmates to believe what we believe."

It is the hope of reentering society that boosts the spirits of guards and inmates alike, but none of them knows whether the outside world is ready to accept them.

Despite repeated campaigns by the government and NGOs, prejudice and discrimination are still rife among the general population.

A recent survey conducted among 12 universities in Beijing, considered to be the most enlightened city in the country, showed that nearly a quarter of the students object to having HIV-positive classmates, and 4 percent say that HIV carriers should not even be allowed to have a job.

The survey shows university students still consider it a "challenge" to shake hands with or embrace a HIV carrier. Once they finally do it, they regard it as a "breakthrough" in life.

The attitudes of the outside world hurt the HIV-affected inmates in the Qingliu Prison.

Fan recalls a China Central Television news program about the life of China's AIDS victims. The inmates were deeply depressed when they saw AIDS patients being disowned by their families and their possessions, such as clothes and bed covers, being burnt.

"They feared that what they saw on TV would happen to them," says Fan, adding that less than half of the HIV-positive inmates revealed their test results to their families. For most, it is a secret only known to other inmates and certain guards.

Fan says that the letters of former inmates who wrote to the prison after being released - and confronted with the prevalence of social prejudice - were often distressed and confused.

"The rehabilitation of an inmate will certainly suffer if he or she encounters discrimination, whether it is inside prison or outside," says Jing Jun, an HIV policy professor at Tsinghua University. "We need to carry on the campaign to fight discrimination both in prisons and among the general public."

Wu Zunyou, a top HIV/AIDS prevention specialist at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, says a lack of continuity of care and medical support will harm progress made in HIV/AIDS prevention in prison and could lead to new transmissions.

"People living with HIV/AIDS need regular counseling or to at least have somebody who cares about them and whom they can talk to," he says.

Huang Yiquan, head of the Qingliu Prison, says prejudice and ignorance about AIDS carriers are so strong that he had to postpone an expansion plan for the ward.

"The present ward is almost full and badly needs to be expanded to accommodate newcomers. But the problem is that almost all of the construction teams went off the job the moment they were told HIV carriers once lived here," he says.

The rural construction workers probably believed the virus could live in the empty wards weeks after all the inmates had been moved out, Huang says with a wry smile.

Prejudice also explains why Fan prefers to keep a low profile. He insisted reporters not take close-up photos of his face and requested he be identified only by his surname if the story is printed in Chinese.

"Except for my wife, I haven't told any of my family or friends outside Qingliu Prison about what kind of inmates I look after," Fan says, speaking in a low voice with his eyes closed and his head down. "Even my parents don't know. If they did know, they would probably worry obsessively."

Xinhua correspondent Liu Jiajing contributed to the story

(China Daily 07/09/2007 page8)

|

||

|

||

|

|