E'gao: Art criticism or evil?

By Wu Jiao (China Daily)Updated: 2007-01-22 07:17

The Ministry of Culture aims to rein in a recent trend on the Internet - the parody of popular music and songs by netizens.

| |||

The regulation, however, does not extend to movies, plays and other historical works.

The regulation is at present targeted at a new art form called e'gao, popularized by such groups as the Back-Dorm Boys from the Guangzhou Art Institute in South China's Guangdong Province.

By using Western pop songs as background music to their videos, the face-making, lip-syncing duo has caused quite a craze on popular websites such as YouTube (www.youtube.com ).

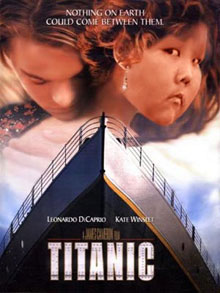

The photo of a Shanghai teenager boy is photoshopped to a Titanic poster. [file] |

The character "e" means "evil," and "gao" means "to make fun of". Combined, the phrase means a new multimedia expression that makes fun of original works, often with malicious intent.

The word e'gao is so new it is not even listed in Chinese dictionaries.

However, it can be traced to the Japanese word "kuso", the definition of an Internet subculture that deconstructs serious literature or artistic materials to entertain people.

Of course, Kuso has many meanings, depending on the context: "Damned", "funny", "nonsense", "idiocy", "feces" and "mischievous tricks" are just some of them.

In Taiwan's Internet subculture and video gamers' communities, Kuso has evolved into a new attitude towards life that suggests "making fun of everything and playing practical jokes". It has no agenda or logic.

Since being adopted by the Chinese mainland in early 2002, it has become a popular form of entertainment and got the name e'gao.

From prime-time TV programmes, mobile phone text messages, to online chatrooms, it is difficult today not to watch, read or hear e'gao.

Examples of E'gao

The latest example of e'gao is the re-designing of the Olympics emblem on the Internet, which adds a skirt to the human-like figure inside the circle of the emblem and indicates it a female version compared with the skirtless male version.

The organization committee of the 2008 Olympic Games already announced last Wednesday that the girly version of the emblem actually violated their copyright and harmed the Olympic spirit.

Also, one typical example of e'gao is the recurrent use of the face of Xiaopang (little fatty). The rotund Shanghai gas station intern has become an unexpected celebrity after a picture of his face was posted on the Internet.

His face has been superimposed on Leonardo Dicaprio in Titanic and Russell Crowe in Brave Heart, provoking much laughter both at home and abroad.

According to a Beijing computer professional surnamed Lin, the re-use of little fatty's face has become a competitive platform for many computer talents including himself.

But e'gao does not only use photography videos, plays, novels and songs can also be vehicles.

The latest examples include the remarks of popular TV soccer commentator Huang Jianxiang.

During the Italy-Australia match at last year's World Cup, Huang's emotional outburst over the winning goal by the Italian team not only caused an uproar among Chinese viewers and netizens but also gave rise to a number of short Internet audio and video e'gao pieces.

His comments were also turned into humorous mobile phone tones that were downloaded by millions of users.

Huang's outburst was blamed on his huge work pressure. Likewise, many urban Chinese now suffer from the same pressure. Jobs are more challenging than ever before and overtime is often the order of the day.

As for the Back-Dorm Boys, they have been so successful in attracting millions of netizens that they recently signed a five-year contract with Taihe Rye Music, a Beijing talent management company that boasts several famous pop stars.

"We want to do movies, ads, music, abstract art, everything," said Huang Yixin, one half of the duo.

Reasons for its popularity

While e'gao has been so popular, almost every e'gao fan has their own reason for their fondness.

A Peking University student, Wang Xiongjun, said: "E'gao is an art criticism loved by people.

"It is a vehicle for people to deconstruct burning issues. It is an interesting, spiritual pursuit," said Wang.

For instance, The Bloody Case Caused By A Steamed Bun, an Internet parody of the mega-budget film The Promise enabled its creator Hu Ge to immediately become an e'gao luminary early last year.

In some people's view The Promise was a deserving target when it failed to deliver on the promises made in its promotional campaign. And Hu's short e'gao video provided an outlet for the public.

Hu gained much popularity when the director of the film, Chen Kaige, threatened to sue him for piracy.

According to Xia Xueluan, a sociology professor at Peking University, people need ways to let off steam when under pressure and e'gao meets this urgent need.

"Especially today many youngsters live under constant pressure and find no solution to their social problems, they need an outlet to vent their frustrations," Xia said.

Xia also defines e'gao as a subculture characterized by satirical humour, revelry, grassroots spontaneity, a defiance of authority and mass participation.

But Cao Weidong, vice-dean of the School of Literature at Beijing Normal University, sees the popularity of e'gao in a more sophisticated angle.

The underlying reason behind the popularity of e'gao is that consumerism is so widespread that even life's values have been commercialized to appeal to the general public, said Cao.

In addition to cultural background, the speed of the Internet, according to computer professionals, is the best platform to promote e'gao-related material.

"It can reach millions of Internet surfers within a day. It can also boost the profits of websites," said an employee of a leading news portal, surnamed Zhang.

Voices of disapproval

While many enjoy e'gao, there are those that do not. The latter feel it must be stopped as it affects China's culture.

"At first, I enjoyed the videos, but one made me really angry. It was about a heroic figure who died in the 1920s revolutionary war," said Zhao Jing, a white-collar worker in Nanjing.

Zhao was referring to an e'gao video which depicts a revolutionary-minded child as a vicious one, and his brave father as a trumped-up real estate developer.

"Popular culture should not be vulgarized nor should it be used in any fashion simply to please the public," said Xia of Peking University.

"If entertainment becomes totally ridiculous, our cultural heritage will suffer," Xia said.

Among those disapproving, the supposed negative influence of e'gao on the underage group is of the prior concern.

According to Zhang Yan, a teacher at Nanjing University, most children already know little about the hardships revolutionary leaders underwent to achieve today's peace and prosperity.

"They will become even less aware after watching distorted e'gao material of heroic people.

"If this falsehood becomes the truth in the future, it will be a major tragedy for the country," Zhang said.

Also, according to many legal experts, e'gao infringes privacy, image, and copyright laws.

To control the trend, they proposed website operators should play a more positive role in regulating the virtual world and help control the spread of malicious e'gao material.

However, some websites are more concerned with economic benefits, than with the proper regulation of material.

Online music is one example.

According to the Ministry of Culture, online music, including the e'gao ones, generated 2.78 billion yuan ($360 million) last year.

It exceeded the amount derived from online games, e-businesses and online video services, according to the ministry.

To counterbalance the popularity of e'gao, Sun Guoqing, a TV program host, suggested there should be more TV talk shows with participation of netizens to divert them away from the virtual world.

Facing such a situation, the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television has vowed that it would exercise more control on the use of e'gao material.

The warning, as well as the new regulation by the Ministry of Culture, has won public support as well as disapproval.

According to Xia of Peking University, it is difficult to define the legal boundaries of e'gao.

"It depends on the public to decide the fate of a media product, not the ministry. It is also difficult to determine which one will be welcome or not," Xia said.

|

||

|

||

|

|