It's no exaggeration to say the evolution of China's hospitality industry during the past 30 years is a prime example of how the nation's economy has also progressed.

As the history record shows, dating back to the Shang Dynasty (1,600 BC-1,046 BC), there were accommodations for travelers in China, though the facilities markedly changed over the next 3,000 years.

After 1949, when the People's Republic of China was founded, the government turned a few buildings into guesthouses to house the then few foreign visitors and delegates. But most looked shabby from the outside, and were sparsely equipped.

An exception was the State-owned Beijing Friendship Hotel founded in 1954 and used primarily to house foreign notables, journalists and businesspeople.

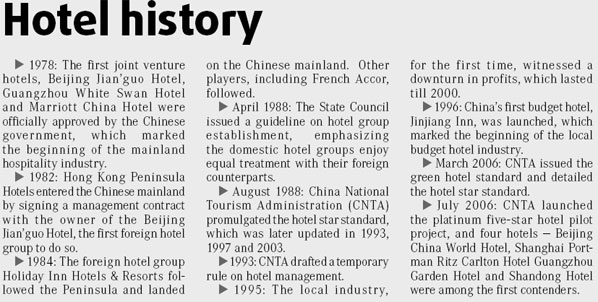

About three decades later, the concept of a "star hotel" - already common in Europe and the United States - arrived in China shortly after 1978, when the country's opening-up policy began.

The then administration in charge of China's tourism industry decided to build eight Chinese-foreign joint venture hotels in the mainland's three cities - Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou - to meet the needs of the growing amount of overseas businesspeople and more discerning tourists.

It signaled the beginning of China's modern hospitality industry.

But exactly which luxury hotel was first approved by the Chinese government has long been debated in the hospitality circle. Was it the Guangzhou White Swan or Beijing Jian'guo Hotel?

The 843-room White Swan was co-invested by Guangdong government and the Hong Kong entrepreneur, media baron (South China Morning Post) and philanthropist, Henry Fok Ying-tung, with an initial investment of $49 million. In July 1979, the two sides signed a preliminary agreement and the building opened in February 1983.

What motivated Fok to make such a bold decision was not the hope of quick profits, but his belief in the progress of China's reforms. He personally got involved in everything from site selection to the hotel's design, construction and management style.

When the hotel opened, Fok insisted the hotel must be open to all which encouraged slews of local residents and visitors to come around to come to simply hang out in the lobby, where they often snapped pictures of the 10-meter-long waterfall.

Amazingly, the hotel made a profit during its very first year of operation, and now is still one of the most popular five-star hotels in Guangzhou.

But more people cite Beijing's Jian'guo as the first post-reform posh hotel property, a fact also confirmed by Shao Qiwei, director of China National Tourism Administration, who, after searching the old files, confirmed it in early 2008 during a small gathering.

The 468-room Jian'guo hotel was a joint venture by the Beijing government and a Chinese- American entrepreneur named Slam Chen who had been working in the American hospitality sector, with the former holding 51 percent shares. Located in the CBD (central business district), the hotel opened earlier than White Swan, in April 1982.

But unlike the White Swan, Jian'guo employed an international hotel group, Hong Kong Peninsula Hotels, to manage its operation, the first to do so.

According to Chris Lu, general manager at New Otani Chang Fu Gong Hotel in Beijing who was appointed by the then tourism administration to join Jian'guo in 1981 and started as vice-director of the food and beverage department, the Peninsula brought in and applied an extremely strict training system. The hardcore hospitality education process went from hiring people to training them and stirred up strong opposition among the local employees.

"Many believed it was an insult to be pressured so much to keep smiling all the time, to stand up straight continually, and to speak fluent English," he says. "They grumbled that it was absurd to spend so much of the hotel's reserves (3-5 percent of the revenues) on the Peninsula group," says Lu.

But the attitude changed when the hotel showed robust growth, gaining 1.1 million yuan even in the first seven months, despite the high room rates, twice of that of the Beijing Hotel. And the employees' salary was also attractively high, twice to three times above the average.

Jian'guo's success stimulated many other hotel property owners to follow suit in partnering with international hotel groups.

The US-based Sheraton Hotels & Resorts (Sheraton) was the second after the Peninsula that was invited. Sheraton's first management deal in the mainland was the Great Wall Sheraton Hotel, located along the East third-ring road in Beijing's CBD. The hotel had originally opened in 1983, but its business was poor until 1985 when the owner contacted Sheraton and both sides signed a management contract. And the business recovered very soon.

Following the Sheraton came in the United Kingdom-based International Hotels Group and Hong Kong-based Shangri-La in 1984, the French Accor in 1985 and the US-based Hilton in 1988. Shangri-La was one of the few that held equity in most hotel properties, but since the 2000s the group also began to turn shift to the management business.

In the 1980s, to accommodate the growing foreign travelers, a batch of hotel properties besides the eight officially appointed ones were erected around China's major cities.

But the industry was in its infancy, and the majority of the hotels were under the management of the Chinese who were still groping their way ahead.

To standardize and improve the facilities and services, China National Tourism Administration, in 1988, issued the "star hotel rating system", which signaled that the local industry had entered a new era when hotels were defined and rated by stars.

Room oversupply

Driven by China's economic rise, especially from 1996 to 2000, real estate developers set off a hotel building wave where the numbers hit historical highs, though the industrial revenue numbers fell to record lows.

From 1996-2000, also China's Ninth-Five Year Plan period, the GDP (gross domestic product) enjoyed an annual growth rate of 8.1 percent. Encouraged by the high return on investment of 20 percent in the hotel business, both State-owned institutions and private ones swarmed to hurl themselves into building hotels.

By the end of 1990, the number of hotels in the mainland rose to 1,987 from 203 in 1980, but the figure rocketed up to 10,481 in 2000 and the hotels possessed a total of 948,200 rooms.

About 354,000 of the rooms were added during the 1996-2000 period, and the annual growth of rooms was 12.39 percent, which was, however, three times of the growth of hotel guests nationwide over the same period, standing at 4 percent.

Most hotels copied from each other's designs and services and were so busy trying to grab guests by lowering room rates that beginning in 1996, the hotels' occupancy rate and profits on average nationwide began dropping and fell to the bottom in 1998, before rising a little in 2000.

Budget hotels, which originated in the US in the 1940s also showed up during that period.

China's first budget hotel brand was Jin Jiang Inn, which was created in 1997 by Shanghai Jin Jiang International (Group) Company Ltd, a Chinese leading hotel group.

In April 1998, another brand, New Asia Star, was launched, also in the eastern city, which was followed by East Ravel in 1999 and Home Inn in 2002. In 2000, the budget hotels numbered 60,000 with 3 million rooms.

The budget hotel concept came at a time when the local tourism industry was taking shape in the late 1990s, stimulated by the rising individual incomes and the policy of the three golden-week holidays in May, October and the Spring Festival issued by the Chinese government 1999.

During the 1999-2005 period, the number of domestic travelers had risen from 40 million to 110 million. Compared with four- and five-star hotels, budget hotels are cheaper and no less comfortable.

Since 2000, foreign players such as Super 8 and Ibis also joined the wave. The powerful sales networks, management techniques and plentiful funds helped them quickly gain an upper hand.

This pressed the local players to partner the venture capitals (VCs) or get listed for faster expansion and better corporate governance. In October 2006, Home Inn took the lead in listing itself overseas in NASDAQ, and it is now China's top player by having 400-odd hotels. Home Inn and a number of other brands including Jinjiang Inn, 7 Days Inn and Hanting also raised handsome funds from the international VCs in the past few years.

The local budget hotel industry grew almost overnight. By 2007, it is estimated there were 100 budget hotel brands that owned 1,000 locations nationwide.

But such volume was still not enough and there was a huge potential to tap, given that the ratio of budget hotels to the posh hotels as a whole in China, at below 10 percent, is far less than that of the developed nations, usually around 70 percent.

A booming industry

The past seven years witnessed a "genuinely healthy and prosperous hospitality market" in the mainland, which is expected to continue for the next decade, says Michael Issenberg, chairman and chief operating officer of Accor Asia-Pacific, the French hotel giant which has launched six brands in China.

By the end of 2007, there were 13,378 hotels in China, a minority of which were four- and five-stars with fairly high occupancy rates ranging from 70 to 75 percent in major cities.

All the international hotel management leaders have piled in and play the major roles. They not only brought in a package of brands tailored to all levels of guests, from four- and five-star to economy and business apartments, but also aggressively expanded the local network, from the key gateway cities to the secondary- and third-tier cities.

Take Accor. Its six brands in China, include upscale Sofitel, and Pullman, midlevel Novotel, apartment brands Mercure and Suithotel and budget brand Ibis. Its plan is to obtain a portfolio of 180 properties around China by 2010, says Issenberg.

"China's hotel industry is probably the most exciting worldwide, and in 2011, it will become our largest around Asia," he says.

Accor's view is typical of its global peers. Many attribute it to the Beijing Olympics in August, Shanghai World Expo and the Guangzhou Asia Games for 2010. But the players don't take it for granted. "Accor's strategy is never based on the Olympics," Issenberg says.

It was the increase in frequent business traveling resulting from China's entry into the WTO in 2001 and the nation's rising economy, which give them the confidence.

The past three decades has also seen the growth of 180 domestic hotel management groups, but except for Jin Jiang, Beijing Tourism Group and Home Inn, few can boast of being qualified enough to compete against their foreign peers.

"Few have the patience to develop the brand from a long-term perspective," says Lu. And Issenberg adds, "language is their biggest problem".

For both domestic and foreign brands, "a talent shortage" is now the biggest challenge ahead. "Ten years ago, people are proud of working in the hotels because of the higher salary, but it is misery now. Hotel jobs are more demanding but less competitive in pay," Lu says.

Many international hotel groups including Shangri-La and IHG have set up the training academies in the mainland to make up for the crunch. Issenberg says Accor is also working on this because "training is the crucial thing".

(China Daily 05/19/2008 page2)