Laying strong foundation in realms of amphibians and reptiles

Researcher gives new dimension to herpetological research

In 2010, Wang Yingyong, a senior researcher from the School of Life Sciences at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, and deputy director of the school's herbarium, led a group of students to conduct a biodiversity survey in the Jinggang Mountains in Jiangxi province.

It was October, and winter had already set in. The project was divided into two groups: one focused on bird and mammal surveys primarily working during the day, and the other on amphibians and reptiles mainly busy at night.

After each survey, Wang and his students meticulously organized the data, checking the photos the surveyors had taken and their audio recordings.

During the process, Wang stumbled upon a photo of a juvenile tree frog. The photo was taken at 7:20 in the evening, Wang recalled, adding the area belongs to the central part of the Asian subtropical region.

According to the data available at that time, Wang said, the primary distribution area of the type of the tree frog was in the southern part of the Asian subtropical region, with the nearest known distribution area to the Jinggang Mountains being the Dayao Mountains in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, nearly 1,000 kilometers away.

It was evident that the frog in the photo was far from its known habitat. The discovery led Wang and his students to suspect that the frog could potentially be a new species, sparking a long journey of discovery.

"Before the survey, my research mainly centered around birds and mammals," Wang, 58, told China Daily. However, as the quest to identify the enigmatic tree frog unfolded, the researcher uncovered many gaps awaiting exploration within the realms of amphibians and reptiles.

Over the next thirteen years, Wang and his team members traveled to 210 spots across the country and discovered 68 new species of amphibians.

Currently, there are over 670 species of amphibians distributed in China, with more than one-tenth of them being species discovered and named by Wang and his team during this period.

Search for elusive

The photographer of the photo was a volunteer of the survey who informed Wang that the photo was taken in a mountain marsh at an elevation of 1,520 meters above sea level. Wang and his students immediately set out to this location to search for the frog.

The journey from Jinggangshan town to the site took a 40-minute drive, followed by a trek through a large stream and a bamboo forest before reaching the marsh in the valley. But they failed in their first attempt.

Despite the challenging terrain, they persisted in their search for this elusive frog, making over 40 trips from 2010 to 2014, yet they were unable to catch the frog depicted in the photo.

"It was a little frustrating," Wang said. "Thankfully, we often harvest unexpected discoveries while exploring in the wilderness. I believe that they have arisen from our perseverance over time."

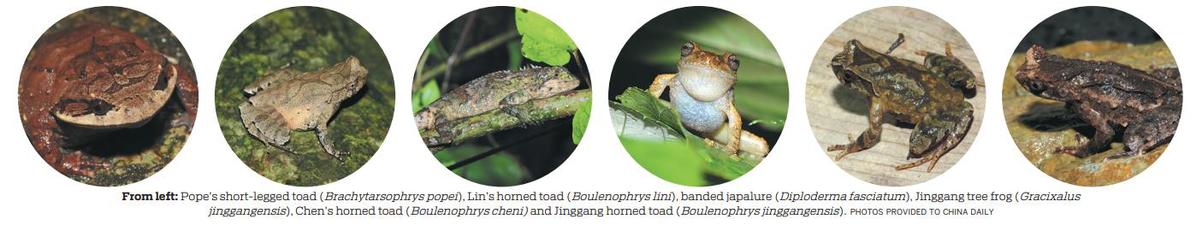

Although they didn't find the specific frog they were looking for, they unexpectedly discovered three species of horned toads. These horned toads belong to a diverse Asian frog genus, which consists of forest-dwelling frogs with unique morphologies. The genus continues to see ongoing species diversification, with new species being described regularly.

When the Jinggang Mountains were on the way to be designated as a national nature reserve between 1980 and 1990, surveys of amphibians had been conducted.

Two species of horned toads were recorded in the area. However, the three species of horned toads discovered by Wang and his team differed significantly in morphology from the previously reported species. "So we classified the three new species as unknown," Wang said.

Another unexpected discovery occurred near the parking area at their first attempt to find the tree frog. In a stream, the team found a large frog that was capable of consuming a bat due to its large mouth. The frog, Wang said, nestled in crevices formed by rocks, emitted a call similar to that of a duck, carrying far distances.

Despite being identified as a toad belonging to the Brachytarsophrys genus, Wang and his team were unable to determine its specific species and could only classify it again as unknown.

On July 27, 2014, a heavy rainstorm hit the Jinggang Mountains during the day. Although their surveys were typically conducted at night, they ascended after the rain stopped, encountering flooded areas with grasses flattened by the deluge.

After numerous surveys during the years, the marshland had transformed into a large waterlogged area. To navigate the terrain, they placed a round log across the water.

The wet tree trunks made the path slippery. As one student walked ahead of Wang, followed by several others, the student in front slipped and fell into the marsh. When they all stopped, Wang turned back to caution the other students and suddenly noticed a lizard. Previously belonging to the genus Japalura, it refers to the genus Diploderma. Lizards of the genus were originally believed to be exclusive to the mountainous regions in Southwest China, such as in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces.

Its presence in the Jinggang Mountains posed a puzzling question of how it had arrived there. The lizard also became a new discovery for the team.

Wang initially thought this might be the day's most significant find, but as they retraced their steps from the marshland back to the bamboo forest at an elevation of 1,200 meters, they unexpectedly encountered the tree frog depicted in the 2010 photo.

Due to the heavy rain, the slender tree frog had sought higher, drier ground. Although it was amphibious, it also had a fear of water, especially in heavy rainfall. Consequently, it had moved to higher ground, which led to the chance encounter.

With the discovery of the first tree frog, they now had a location to conduct targeted surveys. However, to publish a new species, they needed at least four to five specimens, prompting them to continue their search. From July 27, 2014, to 2016, they returned multiple times to the bamboo forest to search for the frog. With the discovery of a single frog and knowledge of how it croaks, they could track it using its vocalizations. Despite the elusive nature of its croak, which often shifted directions, they persevered through the dense forest.

They realized their initial mistake in timing, as the tadpoles of this frog were found during the spring breeding season, not in autumn as they had assumed. This realization led to a breakthrough in their search, as they encountered numerous frogs croaking in the bamboo forest in spring. Subsequent molecular genetic analysis confirmed the discovery as a new species — Gracixalus jinggangensis. In 2017, the species was formally published.

Fill the gaps

In the process of identifying the unknown horn toad species, Wang found that a large portion of type specimens of the amphibians distributed in China were collected decades or even centuries ago and lack molecular genetic information available for researchers to use for species identification.

"To identify the unknown species we discovered during the years, we realized that we need to collect molecular genetic information of many amphibians in the country by ourselves," he said.

"Except those originally found in Southeast Asia, we sorted out more than 300 amphibian species as our targets and launched our collection of their topotype specimens in 2010."

The researcher explained that taxonomists describe species based on a type specimen. "Type specimens of our targets, usually collected long ago, lacked molecular genetic information," Wang said.

A topotype is a specimen collected in the same locality where type specimens were found. "Through the collection of topotype specimens from our targeted species, we can acquire their DNA data concurrently, enabling us to identify and classify the unknown species we encounter," he explained.

From 2010 to 2022, they conducted repeated collections at over 210 sites across the country where frog type specimens had been obtained. "Our collections spanned from the Xizang autonomous region to the Zhoushan Islands in Zhejiang province, predominantly focusing on the southern parts of the country," Wang said.

Given the varying hibernation patterns of frogs, some hibernate in summer, some in winter, and some are active for only two months a year before hibernating, they often had to visit a site in different seasons. In the busiest year, Wang spent over 120 days conducting field surveys.

Fortunately, their effort has paid off.

Wang and his team, consisting of just around 20 members over the years, have created a database that incorporates four main types of information: specimens of different species, photographs, DNA evidence extracted from the specimens, and recordings of vocalizations. "Through the integration of morphological, molecular and vocal evidence, we successfully resolved the classification issues of the horned toads in the Jinggang Mountains," Wang said.

Their systematic approach laid a solid foundation for the development of the country's herpetological research.

Besides 68 new species of amphibians they discovered and published, they also described and published 19 new species of reptiles. "Many members of my team have become biological researchers after graduating from the university," Wang said.

Wang said that he and his colleagues have sent one specimen of every new species they published to the Chengdu Institute of Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for their collection and research and specimens of 55 species to the Zhejiang Museum of Natural History.

Two years before his retirement, the researcher is busy compiling the volumes on amphibians and reptiles of Fauna of Guangdong Province, an encyclopedia on the region's fauna.

"The country's first published frog was collected in 1765 in Guangdong," Wang said. "It's time to summarize our research on the region's 121 species of amphibians."

chenliang@chinadaily.com.cn